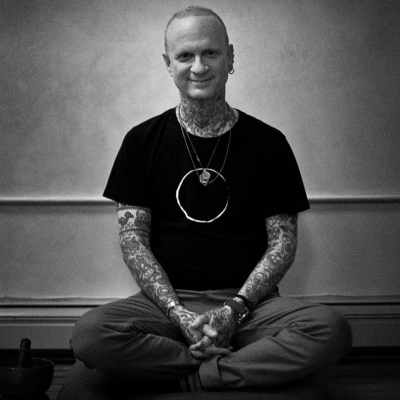

By Jack Korda

The dharma teacher at DharmapunxNYC since 2005; visiting teacher at Zen Care & Against the Stream. Josh’s talks: dharmapunxnyc.podbean.com

As a dharma teacher, part of my work entails providing one-on-one meetings with practitioners in my community, which I’ve been offering for over a decade at the time of this writing (the only unfortunate result is that these meetings have become too popular, and I now have a long waiting list before I can meet with new individuals). Such meetings are private interviews between a student and buddhist teacher.

Unlike what is often offered in the Zen practice of Dokusan, I don’t limit the discussions to one’s meditation practice, but rather encourage people to discuss any issues which are causing emotional distress or intrusive, obsessional thoughts; topics are not limited to the dharma; they can involve a wide array of personal issues, as noted below.

Generally these interviews are straightforward: an individual arrives and describes a challenge they’re experiencing in life, for example disappointing experiences in the search for a loving partners, stressful family relationships, binge eating or drinking, creative procrastination, dissatisfaction at work, panic attacks, mild ongoing depression. Quite frequently, when I suspect a student’s struggles cannot be adequately addressing using buddhist tools, I”ll steer practitioners to some of the talented therapists and/or psychiatrists I’ve come to know over the years; on many occasions I’ve suggested people attend 12 step meetings to connect with others facing similar issues.

What I’d like to discuss here is a different way of perceiving our challenges; most people I meet with consider inner conflicts or struggles as problems, something that is ‘pointless’ and should be ‘gotten rid of as quickly as possible.

Let’s consider procrastination. Suppose someone, whom I’ll call Alice, wants to be a writer, yet struggles setting pen to paper (or typing words onto a laptop). Over months and years Alice might set an intention to produce writing, yet day in and out Alice squanders her free hours on social media, shopping sites or lost in thought. Alice might refer to herself as lazy, self-sabotaging, ‘failing in life’ even. Alice views her challenge–procrastination–as a problem: she believes her procrastination serves no value, is harmful or irrational, is shameful, she believes it means she doesn’t have enough ‘will power.’

Alice, like all of us, has a need to make sense of life, especially when its stressful, so its easy to see a conflicts, setbacks and struggles as an indication that ‘something is wrong.‘

As the buddha noted in many suttas, including the arrow sutta (SN 36.6), the seven bases (sn 22) the great mass of stress sutta (mn 13) and on, every difficult challenge in life contains not only their obvious drawbacks–procrastination causes frustration–but underlying, unconscious justifications as well, reasons sustaining and validating their existence (these unconscious “allures” in the pali canon have many names, including palobhana).

In other words, all of our challenges have deep, compelling explanations for their existence; part of Alice created her procrastination for a reason, to meet a purpose, even though Alice might not be aware of the purpose. While our conscious minds demand that we change and ‘get better,’ our unconscious mind wants to stay safe and not risk change.

My priority is to help people understand the unconscious–emotional–reasons operating beneath people’s challenges, so they can take those needs into consideration as well.

So what could be the purpose for procrastination? Suppose, talking with Alice, we ask her, without thinking too much, to freely bring to mind everything she emotionally connects with writing and “being creative.” At first Alice may well block the exercise, but with a little sympathetic encouragement she starts to free associate and, along with positive ideas (writing means to feel her voice is heard by others) she also expresses feelings of ‘risk’ and ‘vulnerability.’ Like so many of us, Alice experienced times in grade school where she sang, danced, drew a picture or recited a poem she authored and was ridiculed by her peers or siblings; perhaps even criticized by a parent or a teacher.

In other words, some time in the distant past Alice created an emotional belief that being creative can lead to social exclusion and scorn. So as an adult, when Alice sits down to write, her unconscious, emotional mind–which speaks through the body and moods–creates feelings of anxiety, for being creative has been experienced as risky. The anxiety, in turn, leads to procrastination; she unconsciously chooses to look at her Facebook page, for that activity doesn’t feel risky and reduces her anxiety. As the Buddha noted, understanding the allure of our challenges is part of a process of seeing things completely, as they really are (yathabhuta ñanadassana).

In other words, what Alice views as ‘problem,’ her procrastination, is actually a solution; a way to avoid risking rejection by others.

Once we understand the allure of a challenge, we can locate the way out: the allure of Alice’s procrastination is that it prevents her from the risk of being creative, which may entail future rejection. So the escape is for her to keep in mind, as she sits down to write, that she doesn’t have to show her writing to anyone, or for her to note she can limit sharing her compositions with supportive friends. No matter how little Alice writes she can reward the effort with then looking at her social media, emotionally connecting creative writing with reward.

Another example those of us who worry and catastrophize, if we understand the allure of worrying is that it distracts us from the physical sensations of anxiety and offers the sense of being prepared, we can alleviate these emotional needs by keeping in mind all the times in life we’ve been caught off guard, entirely without preparation, by bad news and survived. Or by connecting deeply with other people, so that no matter what we’re faced with in life we’ll feel the sense of support.

In short, getting ‘unstuck’ in life requires a perceptual shift, wherein we stop judging our ‘issues’ as failings, and instead learn to compassionately understand the underlying reasons beneath our struggles, we can proceed to creatively solve how we move forward an alleviate the fears of the heart.

Copyright ©2015 TheHuffingtonPost.com, Inc.