By Michael Chender

Acting wisely means marrying insight to action. Here’s one approach to help you decide when to act, and when to wait.

Imagine you’ve just been promoted at yourjob in a large organization. That’s the good news. The bad news is that you’re asked to fly tomorrow to sort out problems in a branch office you’ve had no contact with before now. No one is clear what the core problem is, but you are sent there to sort it out—with the power to hire and fire. You are overwhelmed. How do you begin?

When faced with a challenge, we should ask ourselves two questions: “What’s actually going on?” and “What should I do?” How we follow through on these questions will determine the wisdom and effectiveness of our actions, be it with family, work, or our personal lives.

Of course, we all differ in our approaches. Some of us feel more comfortable thinking about the questions that a challenge raises rather than rushing to act. Others prefer acting quickly rather than pausing to inquire. But in order to act wisely, we need to access both clear insight and decisive action. Insight without action is impotent; action without insight is reckless.

What follows is one model for wise action, for how we can respond with the right approach at the right time. It proposes five steps in the life-cycle of an action—Entering, Exploring, Acting, Completing and Letting Go. Each step calls for a different attitude and different skills, and evokes a different aspect of mindfulness.

Entering

When you get to the branch office, you notice that everyone is nervous. Some employees are too friendly, others are wary, and some seem frozen in panic. They’re waiting for something to happen.

It’s easy to get carried away by the energy of your nervousness or emotions and react before you have the necessary information.

But in any new situation, we need to learn before acting. So the first step is to meet the situation with an attitude of “not-knowing.” In practice, this means that our very first act is to do nothing: We simply pause, so we can let go of our psychological momentum and open our senses and attention to the details of the new situation. By stopping that way, we often experience our internal busyness, nervousness, impulsiveness and assumptions more vividly, reducing our chances of allowing them to distort our experience without our realizing it.

This willingness to look freshly despite feeling shaky is what it means to be genuinely “open.” It’s the fundamental attitude of mindfulness practice, allowing whatever comes up in our experience to be there—including our fears and reactions and desire to flee from the spot.

Pausing at this stage doesn’t mean that we simply persist in doing nothing. It means, rather, allowing ourselves to do what the moment calls for without imposing a preconceived idea or reaction on it. Other ways to talk about this are “doing nothing extra,” “not reacting,” “letting the situation reveal itself,” and “welcoming your experience.”

In challenging situations, we must look openly and honestly at the problem at hand—despite our fear of what we’ll see.

This simple step of entering is the hardest to do—but if we miss it we start off on the wrong foot. We can probably think of a number of times we’ve been reactive and jumped to the wrong conclusion. In organizational life, with the pressures of the bottom line and the need to look competent, we waste a huge amount of time and effort because we rarely find the space to see habitual assumptions at the beginning of initiatives. In military terms, this is the “shoot-first-and-ask-questions-later” or the “ready-fire-aim” syndrome.

When you do nothing at the troubled office but display patient interest, there’s a group exhalation, and the atmosphere calms down.

Exploring

Having entered the situation and opened your eyes and ears and cleared your mind, you now need to get to the root of the problem or figure out a way forward.

The main obstacle to exploring challenging situations is the difficulty in looking openly and honestly for fear of what we’ll see and what it may demand of us.

As with entering, exploring demands openness—we need to allow all relevant information in. The key is to explore with genuine curiosity. That curiosity is natural to us. It is present in mindfulness practice when we feel relaxed. It’s a spontaneous sense of interest and friendliness toward whatever arises in our experience. Without some of that inquisitiveness, our inquiry becomes just ticking off preconceived boxes— we’re going to miss a lot.

There are at least four significant ways to explore a situation—through reductive analysis, systemic analysis, body intuition, and pattern recognition. We each use all four, although often not consciously. Most of us rely on one or two, and may disparage the others. But they are all potent in revealing different aspects of the terrain we need to be aware of when acting wisely.

Reductive Analysis

Reductive analysis splits a situation into its parts and looks closely at each, using tools ranging from pro and con analyses to spreadsheet projections and detailed project plans. It’s what we usually mean by “analyzing.”

Systems-Oriented Analysis

Systems-oriented analyses show the more holistic view of how things connect to larger and often surprising patterns. We need to be aware of the wide variety of influences, some not immediately obvious, on our object of inquiry. Among other things, this kind of investigation clarifies the root causes of a problem as opposed to the symptoms, and can reveal unsuspected places where a small action can have a large effect on what we’re trying to achieve.

Body Intuition

On the intuitive side, we can get useful information through methodical attention to the feelings in our body, which includes “gut instinct”—“there’s something off here,” or “I feel that person would be a good ally.” This is a deep listening skill which we can cultivate.

Pattern Recognition

Finally we have the whole area of pattern recognition, or what we can call somewhat romantically “reading the signs.” This is a tricky area that includes synchronicity—“I almost got into two accidents on the way to having the meeting”—meaningful dreams, and more developed or finely tuned intuition. These can easily slide into wishful thinking, but watching and listening in ways we wouldn’t usually is a skill that can bring new and valuable information.

At the office, you interview everyone, review the group’s performance, talk to the main players, begin to get some ideas, and analyze them from a number of different angles, but the situation still feels murky. You sit with this feeling and for no obvious reason begin to feel curious about Carmen, who works in a tech support role with John and had been quiet in the brief interview you had. She doesn’t seem central to the issues at play here, but you casually ask her to drop in again. Sure enough she provides the key.

It becomes apparent that John is quietly at odds with the rest of the team, although no one can ever quite trace the problems to him. You consider the way the team currently works; clearly, John is a major obstacle. You talk to him and discover that the problem is deep-rooted. John has to be let go.

Acting

Ideas and insight are brewing, and at some point the time for observation is over. We need to move from exploration to action. Each stage represents a shift in the feeling and energy of how we engage, and this is the most marked, which is why it’s particularly challenging for many of us. In the previous two stages we were letting it all in. The attitude of broad openness here changes to determined focus, saying goodbye to the world of options and to everything but our decided course of action. “Not-knowing” needs to change to knowing, to a confidence in committing to a course forward. That knowing may feel tentative, but at this point we have to leap.

When is the time to act? There are two possibilities. The one we hope for is that we reach “sufficient” clarity about the next step. The other is a certain kind of energetic hesitation, when we find ourselves again and again actively resisting doing something specific. Part of us “knows” what to do.

Acting requires courage. In the moment of acting we are alone. In fact at that fraught instant of saying the difficult thing, stepping across the threshold, making a definite move we can’t take back, we don’t even have the voices in our head for company. We simply have to do it.

We invoke that fearlessness in mindfulness practice every time we go back to the breath, every time we let go of a thought or obsession. For a microsecond we are stepping into the unknown. It’s a wonderful training for moving into action.

At the end of the exploration stage, the challenge of giving in to impulse is joined by the challenge of getting trapped in hesitation. We might want to figure out how to accomplish our whole vision at once, or seek certainty, or try to do the perfect thing, or be too afraid to make a mistake. “Paralysis by analysis” is a common feature of organizational life.

Both hesitation and impulse are based on fear, which lies behind so much of our obstructing habits. It is commonly understood that the way to work with fear is to look directly at it, to face it. There are many practices of fearlessness—sitting meditation is one. Sports and performing and martial arts can also be excellent training in acting despite fear.

As directly as you can, despite never having done this before and feeling deep discomfort, you tell John you’re letting him go. John seems stunned and then angry. “You’ll be hearing from my lawyer,” he says as he leaves.

Completing

That night you can’t sleep, wondering if you examined the situation enough. By 2 a.m., you’re working on some way to partly backtrack—a consulting contract maybe? But you eventually fall asleep, and when you wake up, things feel simple and clear and you have new resolve. “What was I thinking?” you ask yourself.

As you complete an action, try to uphold your intention in the face of internal and external reactions, remaining calm, steady, and confident as if in meditation.

Right after you make the leap to action, another kind of challenge arises. The initial act is only a first step toward your goal. It starts a chain of consequences that brings often unpredictable reactions and opportunities. Bold action will likely bring you unexpected support and also stir up resistance. Completing the action means working with the initial feedback and deepening the effectiveness of what you’ve done. You need to continue to focus, in this case on your initial intention and on not being caught by the temptation to lose your bearings through reaction.

After the moment of any significant action, we often have immediate inner feedback, our “second thoughts”—the voices in our head that proclaim, depending on our habit, what a great or lousy job we did (“Oh no, I screwed up again,” or “That will show them who they’re dealing with!”). Such feedback distracts us from seeing accurately what’s happening as a result of our action. Habitual tendencies to want to be liked or look for a fight are obstacles here. Again the classic generic advice is “Don’t look back.” That doesn’t mean ignoring consequences; it’s quite the opposite—don’t get caught up in the habitual patterns that blind us.

Then if we are pushing on the status quo or vested interests we’ll also stir up resistance. People may attack us or our plan directly, pretend to go along with us while they try to undermine us, or flatter us and try to bring us into their agenda. This is your reward for challenging the status quo. Social and political activists know this well.

A good piece of general advice in mindfulness practice is that you don’t have to believe your thoughts. While the mind is jumping all over the place, there’s a deeper, unmoving aspect that we try to invoke by an erect and still posture. This is like riding a strong bucking horse and staying upright in the saddle—“holding your seat.” The job in completing is to invoke some of that imperturbable quality, keeping to the intention of your action in the face of internal and external reactions—being or aspiring to be calm, steady, confident. Then you are in a position to begin to differentiate genuinely useful feedback for next steps.

When you arrive at the office the following morning, the parade of people through your door starts. Some want to congratulate you and ingratiate themselves. Some are very anxious, worried about the knowledge that John may be leaving with or the difficulty of replacing him. You don’t say much, but your confident demeanor puts them at ease. Two days later John calls. “Even though I don’t like the way it happened, I was talking to my wife and she reminded me that this is the space and opportunity for change that we both have been talking about for some time,” he says. “I suppose I have to reluctantly thank you.”

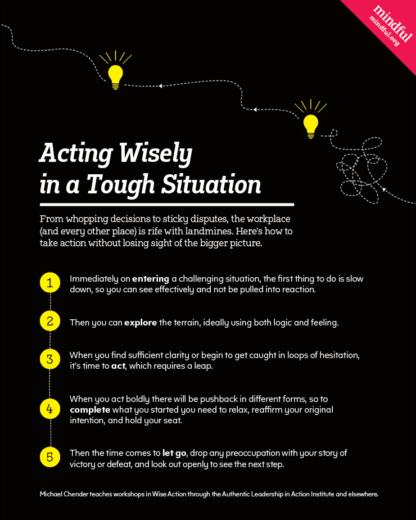

Practice at-a-glance: Acting Wisely in a Tough Situation

1.Immediately on entering a challenging situation, the first thing to do is slow down, so you can see effectively and not be pulled into reaction.

2. Then you can explore the terrain, ideally using both logic and feeling.

3. When you find sufficient clarity or begin to get caught in loops of hesitation, it’s time to act, which requires a leap.

4. When you act boldly there will be pushback in different forms, so to complete what you started you need to relax, reaffirm your original intention, and hold your seat.

5.Then the time comes to let go, drop any preoccupation with your story of victory or defeat, and look out openly to see the next step.

Letting Go

Finally, the action is completed, the dust has settled, and it’s time for whatever’s next. It’s time to let go. How do we know when that is? If it hasn’t already happened, we may find ourselves caught up in the intensity of what we just went through, constantly reliving our victories or nursing our wounds. In either case we’re fighting past battles and need to move forward.

Letting go is not just about releasing. It’s about gathering our strength and moving energetically forward to the next phase of engaging. We can now see more clearly the useful feedback we need to explore our next steps.

In the same way that we often mark important transitions in life with ritual, it’s good to mark the end of a journey with a definite moment of celebration, even if it’s as small as saying to yourself, “Okay that’s done. Let’s look around and see what’s happening.” There’s a natural joy and energy in that. In mindfulness practice we sometimes feel a spontaneous moment of freshness, a breeze of delight as if a big window had just opened in our stuffy room and our preoccupations of a moment before blew right out.

So letting go here involves dropping the whole story and again looking out openly. Focus moves to openness, and we are back at the beginning of the cycle, ready to enter again. In doing that we experience freshness and perhaps a sense of potent eagerness, delight in living in the challenge.

A few days after John’s call, your partner says that you seem a bit distant and edgy. She’s been trying to talk to you and not getting through. It’s true: You’ve been playing the events over and over in your mind—basking in your sense of power and cleverness. You exhale loudly, smile at the ridiculousness of the omnipotent fantasies you’ve been spinning, and decide to take the rest of the day off, before starting afresh tomorrow.

Michael Chender teaches workshops in Wise Action, with master big brush calligrapher Barbara Bash, through the Authentic Leadership in Action Institute and elsewhere.

Mindful celebrates mindfulness, awareness, and compassion in all aspects of life—through Mindful magazine, Mindful.org, events, and collaborations

© 2015 FOUNDATION FOR A MINDFUL SOCIETY