We could all do better. Self-improvement, though, is easier said than done. Attempts to change can feel like battling our own nature—lots of pain and little gain. This post explains how to be smart, strategic, and gentle about self-directed change, so this intriguing project produces real benefits.

A Question of Balance

Moderation and balance are the keys to what philosophers call virtue and psychologists call good mental health. Moderation is also the key to personal goal-setting, for at least two reasons: Balanced styles of behavior are effective, and the changes it takes to achieve them are doable.

Balanced moderation is effective because it combines the benefits of opposite kinds of behavior. For example, assertiveness combines the advantage of forcefulness (going after what we want) with the advantage of meekness (not making other people mad), but without the disadvantages of either, because we don’t make enemies and we don’t get walked on.

Great psychologists from Aristotle to Buddha to Marsha Linehan have explained the value of integrating opposite styles of functioning in a balanced synthesis, and they have warned against extreme forms of behavior, which are usually maladaptive. Ancient terms like the Middle Way and the Golden Mean have been joined by a modern term: the Goldilocks Point.

This paradigm doesn’t apply to everything—it applies to personality-related styles or ways of operating, as opposed to traits that are good by definition, like skills, talents, and abilities. We can’t be too healthy or smart, but most personality characteristics become maladaptive when pushed to an extreme.

When goals for change are framed as movements toward balance, these goals become achievable. Instead of trying to function in a radically different way, we keep our basic personality style and make the strategic adjustments needed to improve our outcomes.

On a Scale From 1 to 10, Where Are You?

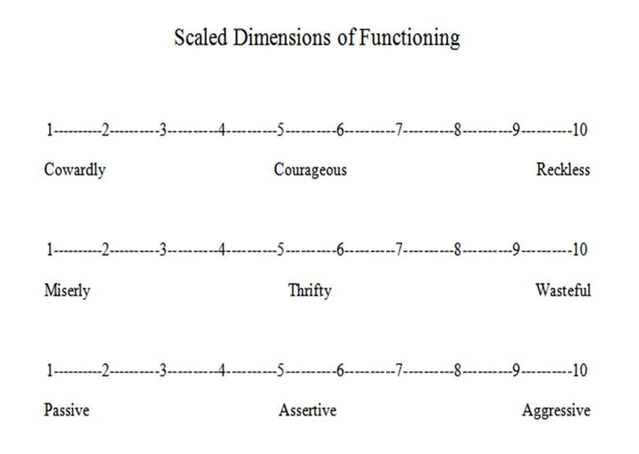

In my work with clients, we often conceptualize the way of functioning they want to change by locating it on a spectrum of possibilities. Ten-point scales are handy tools for this work. Here are three classic examples that will give you the idea:

Scaled Dimensions of FunctioningSource: Shapiro, 2015; 2020

Different people need to move in different directions to reach the adaptive middle, depending on where they start out. For example, highly self-critical people need to become easier on themselves, and conceited people need to become harder on themselves. Rigid people need to become more flexible, and disorganized people need to become more structured.

To begin defining a personal goal for change, it helps to draw a scale from 1 to 10. The first step is to define the dimension of emotion, cognition, or behavior on which you want to change. To do so, think of an extreme form of the psychological style that is not working for you, and write words describing this way of functioning under the 8-10 points of the scale.

Next, describe the opposite way of functioning. Do not just describe the absence of the style (e.g., not reckless, not aggressive, not wasteful)—define the reverse of that way of operating (e.g., cowardly, submissive, miserly). It might help to think about the personality traits you most dislike, fear, or want to avoid. Write words for extreme versions of this style under the 1-3 points of the scale. These words probably describe a personality characteristic that is dysfunctional but in a way opposite the one that has been troublesome for you.

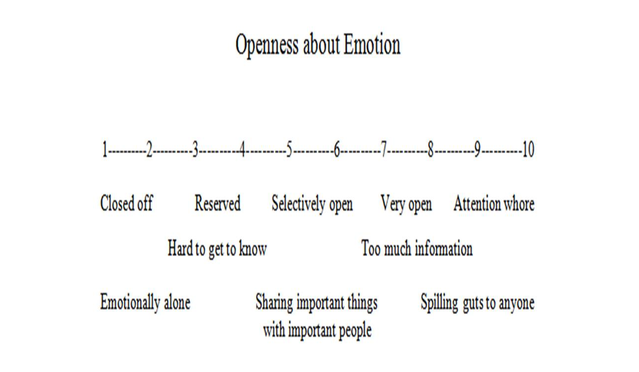

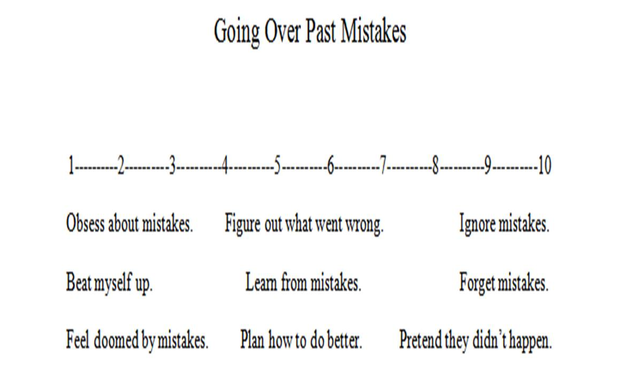

Next, with the continuum defined by its poles, write words or phrases that describe the moderate middle underneath the 5- and 6-points. (5.5 is the exact midpoint.) This style should be a balanced synthesis that combines positive elements from both ends of the spectrum. It might also be useful to describe the two intermediate regions between the midpoint and the poles. Here are a couple of examples:

Openness about EmotionSource: Shapiro, 2015; 2020

Going Over Past MistakesSource: Shapiro, 2015; 2020

Now you are in a position to answer the question: Where are you on this scale? If it’s hard to decide between two numbers, use a fraction or decimal. This number probably summarizes a lot of information in a succinct way.

On a Scale from 1 to 10, What Is Your Goal?

The goal-setting question is, where do you want to be? But before you give your final answer, please consider some questions about what you want and why.

It is useful to ask yourself about the advantages and disadvantages associated with your end of the spectrum. It is almost certain that there are both, because most psychological styles have upsides and downsides.

Think back over the mix of outcomes and consequences that, over the years, have resulted from the way of operating you are examining here. In what ways has it worked well and in what ways poorly? When has this style succeeded and when has it failed? With what kinds of people has it worked well and poorly?

The next question is, what are the advantages and disadvantages of the other side of the spectrum? This side of the continuum, too, undoubtedly has its upsides and downsides. What is this opposite style good for and what is it bad at? What types of situations is it well-suited for, and in what types does it crash and burn?

Next, it is useful to form a mental picture of the adaptive middle of the spectrum and to describe it in words. What are the adjectives that describe the personal qualities at the Goldilocks point? What verbs describe the behaviors taking place there?

Not a Point but a Range

Adaptive functioning does not come in only one form. There are many ways to function successfully—but that does not mean every psychological style works well. There are ranges of effective styles on most personality-related dimensions. These ranges are around the midpoints, but they include more area—more diversity—than the midpoints alone.

In terms of our scales, this means that effective functioning is not limited to a tight band between 5 and 6 but extends outward to a broader range such as 4 to 7 or even 3 to 8. In our search for adaptive moderation, we are not looking for a Goldilocks point but a Goldilocks zone.

The most effective way of working on personal change is not trying to become a different kind of person—not trying to move to the opposite end of the continuum. We don’t even need to move to the midpoint; we can stay on our preferred side and develop a successful style that fits our existing personality and preferences. Realistic, effective goals for change are located in the part of the Goldilocks range that is closest to our starting point.

In scale terms, we don’t have to move from a 9 to a 2; we don’t even have to go from a 9 to a 5.5. If we move from a 9 to about a 7, or from a 2 to a 4, we keep our basic style but moderate it enough to avoid most of its disadvantages and gain many of the benefits on the other side of the spectrum.

This analysis suggests that good qualities, when pushed to an extreme, become bad, and that bad qualities are potentially good attributes that have gone too far. If so, we can turn our faults into virtues by dialing them down, so they move into the Goldilocks zone.

Let’s consider the example of help-seeking. Someone who annoys his or her co-workers by constantly asking for advice and help does not need to eliminate this behavior—in fact, that would be a mistake. Moving from a 9 to a 7 on this spectrum would mean reducing the frequency of help-seeking and asking only when there is a genuine need for assistance. This would probably eliminate the problem, because help-seeking is not a bad behavior—it is a good behavior that can go too far.

With all this in mind, you can specify your goal for change in an accurate, substantive way. Where on your spectrum would you like to be? What is your number?

How far is your goal from your current position? It is probably not as far away as you thought. With this strategic approach, small changes in the ways we operate can produce big changes in the outcomes we achieve.

References

Shapiro, J. P. (2015). Child and adolescent therapy: Science and art (2nd ed.). New York: Wiley.

Shapiro, J. (2020). Finding Goldilocks: An antidote to polarization in personal change, relationships, and politics. Amazon.com Services.

About the Author